A Utah lawmaker has proposed a new idea to mitigate Great Salt Lake dust: build berms to temporarily trap water and form a crust over the exposed lakebed. Once the surface has hardened, that water will be released back to the lake, Utah House Speaker Mike Schultz told Fox13.

The idea might sound like an innovative way to reduce dust and protect public health—but this short-term “solution” addresses only a symptom of the crisis facing Great Salt Lake, risks damaging the lake’s fragile ecology, and fails to grapple with the root of the Lake’s decline—Utahns using too much water.

This kind of geoengineering—altering of the landscape by building man-made berms, dykes, or pipelines—has been attempted at other collapsed saline lakes. At the Aral Sea, attempts to control water flows through complex and costly dyking not only did not work, it accelerated the lake’s decline. Across the globe, humans have tried to build their way out of the problem through afforestation, redirecting rivers, constructing new dams and pipelines and each attempt—no matter how innovative, costly, or complex—has failed.

The only permanent solution to addressing the budding public health crisis caused by Great Salt Lake dust events is reducing human water consumption in the watershed and maintaining the lake at a healthy level.

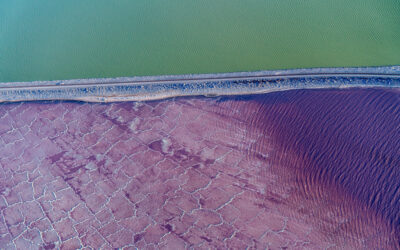

Berming could temporarily reduce dust from certain hotspots, but it is a band-aid solution and comes with major ecological risks. As Great Salt Lake Commissioner Brian Steed told Fox13, trapping water in isolated areas can disrupt the lake’s delicate chemistry. When fresh water is kept out of the lake’s main body, salinity levels can spike. This problem is illustrated by the causeway currently dividing the lake in two, which has created a hyper-saline, inhospitable “North Arm” where only halophiles can survive. Elevated salinity can and do devastate brine shrimp populations and the millions of migratory birds that rely on them. In a system this complex, well-meaning interventions can quickly backfire.

This proposal also diverts attention—and potentially resources—from the only real solution: getting water to the lake. Millions of dollars that would hypothetically be spent on berms and dykes, should be used to fund water markets, wetland restoration, and subsidies for agriculture to switch to more water efficient crops and technologies. Until we address those diversions and secure long-term flows into the lake, dust will continue to blow, salinity will continue to rise, and the lake’s collapse will inch closer. Temporary fixes like berms might be tempting because they’re visible, controllable, and give the illusion of progress. But they’re not solutions.

If Utah wants to avoid the fate of so many other dried-up saline lakes, we need to prioritize what actually works: getting more water to the lake and letting it do what it has done for thousands of years—heal itself.